Explained: Reading the new education policy | Understand the new education policy in the simplest language

Explained: Reading the new education policy

New Education Policy 2020: A look at the proposals on curriculum, courses and medium of learning, and the takeaways for students, schools and universities.

New Education Policy 2020: On Wednesday, the Union Cabinet cleared a new National Education Policy (NEP) proposing sweeping changes in school and higher education. A look at the takeaways, and their implications for students and institutions of learning:

What purpose does an NEP serve?

An NEP is a comprehensive framework to guide the development of education in the country. The need for a policy was first felt in 1964 when Congress MP Siddheshwar Prasad criticised the then government for lacking a vision and philosophy for education. The same year, a 17-member Education Commission, headed by then UGC Chairperson D S Kothari, was constituted to draft a national and coordinated policy on education. Based on the suggestions of this Commission, Parliament passed the first education policy in 1968.

A new NEP usually comes along every few decades. India has had three to date. The first came in 1968 and the second in 1986, under Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi respectively; the NEP of 1986 was revised in 1992 when P V Narasimha Rao was Prime Minister. The third is the NEP released Wednesday under the Prime Ministership of Narendra Modi

Why the National Education Policy is needed

What are the key takeaways?

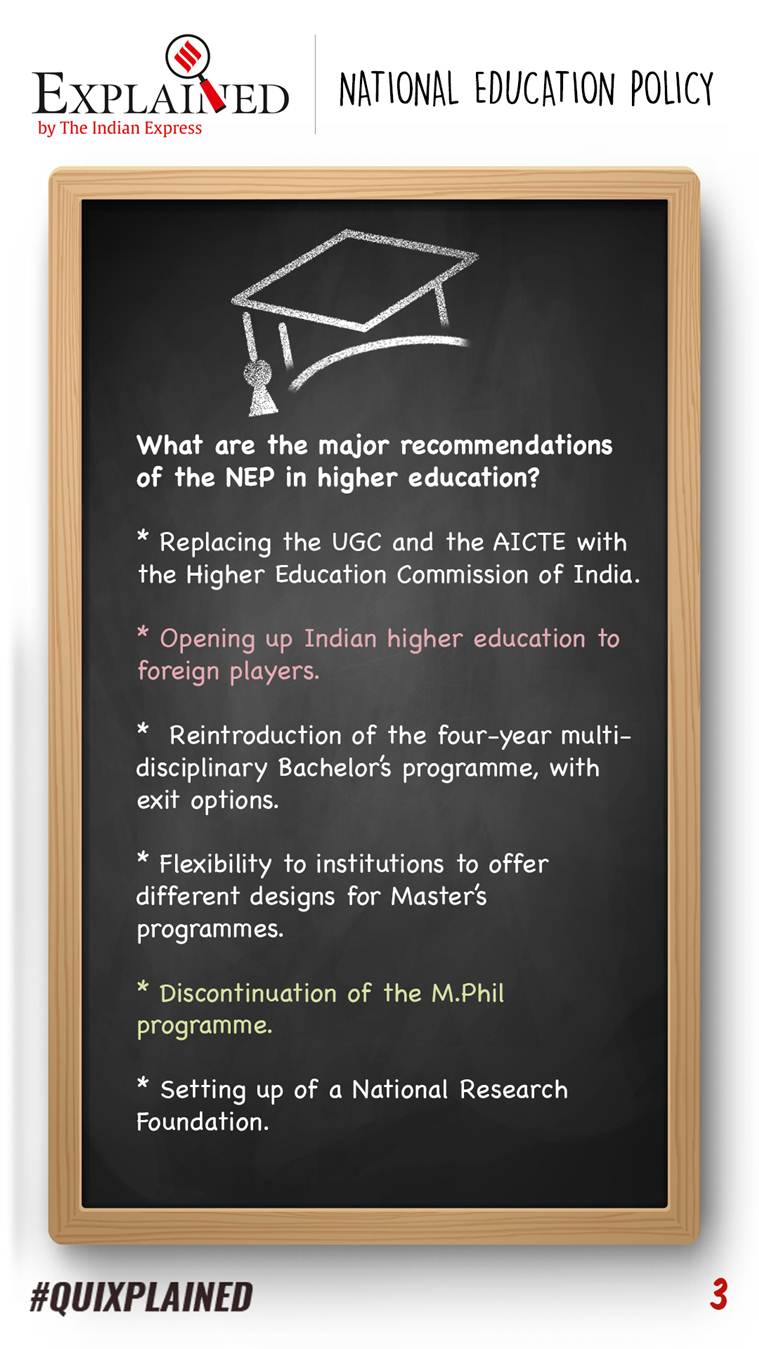

The NEP proposes sweeping changes including opening up of Indian higher education to foreign universities, dismantling of the UGC and the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), the oduction of a four-year multidisciplinary undergraduate programme with multiple exit options, and discontinuation of the M Phil programme.

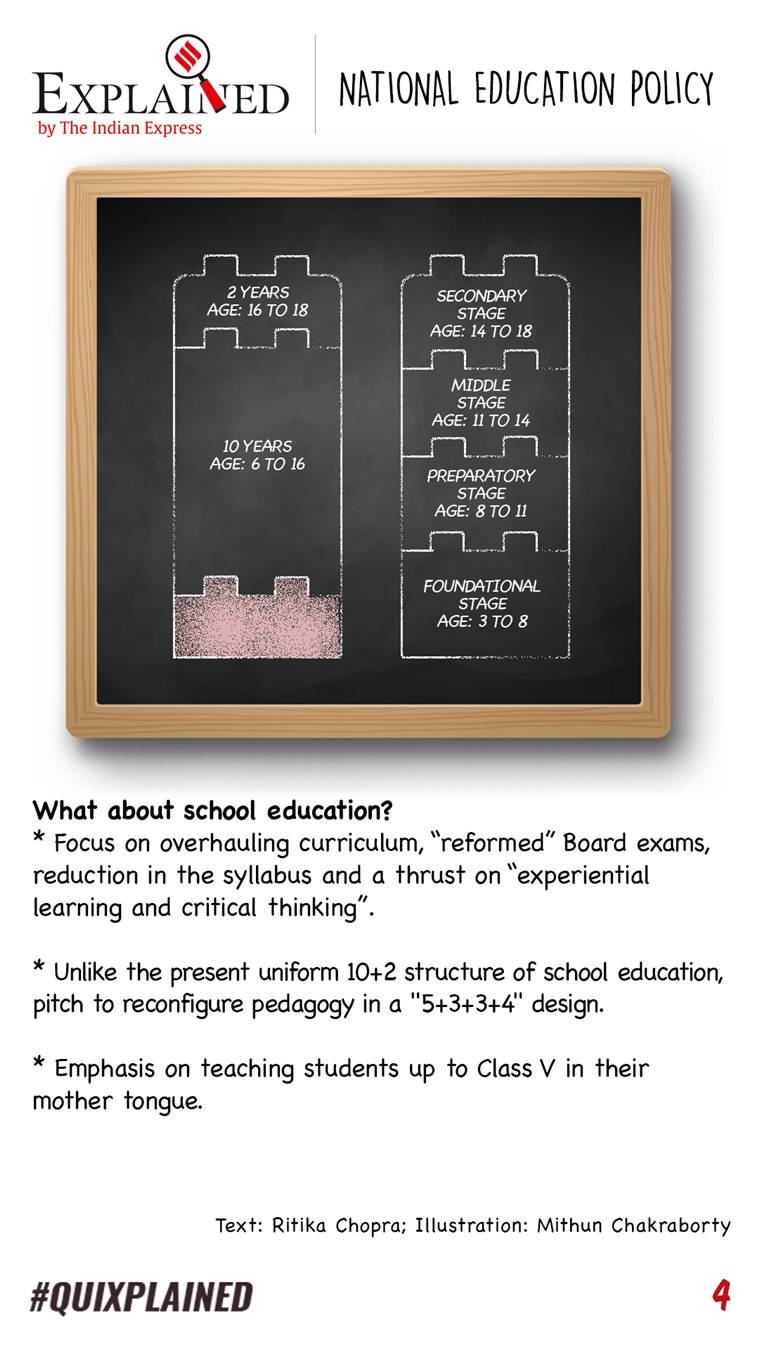

In school education, the policy focuses on overhauling the curriculum, “easier” Board exams, a reduction in the syllabus to retain “core essentials” and thrust on “experiential learning and critical thinking”.

In a significant shift from the 1986 policy, which pushed for a 10+2 structure of school education, the new NEP pitches for a “5+3+3+4” design corresponding to the age groups 3-8 years (foundational stage), 8-11 (preparatory), 11-14 (middle), and 14-18 (secondary). This brings early childhood education (also known as pre-school education for children of ages 3 to 5) under the ambit of formal schooling. The mid-day meal programme will be extended to pre-school children. The NEP says students until Class 5 should be taught in their mother tongue or regional language.

The policy also proposes phasing out of all institutions offering single streams and that all universities and colleges must aim to become multidisciplinary by 2040.

How will these reforms be implemented?

The NEP only provides a broad direction and is not mandatory to follow. Since education is a concurrent subject (both the Centre and the state governments can make laws on it), the reforms proposed can only be implemented collaboratively by the Centre and the states. This will not happen immediately. The incumbent government has set a target of 2040 to implement the entire policy. Sufficient funding is also crucial; the 1968 NEP was hamstrung by a shortage of funds.

The government plans to set up subject-wise committees with members from relevant ministries at both the central and state levels to develop implementation plans for each aspect of the NEP. The plans will list out actions to be taken by multiple bodies, including the HRD Ministry, state Education Departments, school Boards, NCERT, Central Advisory Board of Education and National Testing Agency, among others. Planning will be followed by a yearly joint review of progress against targets set.

Do all states need to follow it?

What does the emphasis on mother tongue/regional language mean for English-medium schools?

Such emphasis is not new: Most government schools in the country are doing this already. As for private schools, it’s unlikely that they will be asked to change their medium of instruction. A senior ministry official clarified to The Indian Express that the provision on mother tongue as medium of instruction was not compulsory for states. “Education is a concurrent subject. Which is why the policy clearly states that kids will be taught in their mother tongue or regional language ‘wherever possible’,” the officer said.

What about people in transferable jobs, or children of multilingual parents?

The NEP doesn’t say anything specifically on children of parents with transferable jobs, but acknowledges children living in multilingual families: “Teachers will be encouraged to use a bilingual approach, including bilingual teaching-learning materials, with those students whose home language may be different from the medium of instruction.

What are its key recommendations?

How does the government plan to open up higher education to foreign players?

The document states universities from among the top 100 in the world will be able to set up campuses in India. While it doesn’t elaborate the parameters to define the top 100, the incumbent government may use the ‘QS World University Rankings’ as it has relied on these in the past while selecting universities for the ‘Institute of Eminence’ status. However, none of this can start unless the HRD Ministry brings in a new law that includes details of how foreign universities will operate in India.

It is not clear if a new law would enthuse the best universities abroad to set up campuses in India. In 2013, at the time the UPA-II was trying to push a similar Bill, The Indian Express had reported that the top 20 global universities, including Yale, Cambridge, MIT and Stanford, University of Edinburgh and Bristol, had shown no interest in entering the Indian market.

Participation of foreign universities in India is currently limited to them entering into collaborative twinning programmes, sharing faculty with partnering institutions and offering distance education. Over 650 foreign education providers have such arrangements in India.

How will the four-year multidisciplinary bachelor’s programme work?

This pitch, interestingly, comes six years after Delhi University was forced to scrap such a four-year undergraduate programme at the incumbent government’s behest. Under the four-year programme proposed in the new NEP, students can exit after one year with a certificate, after two years with a diploma, and after three years with a bachelor’s degree.

“Four-year bachelor’s programmes generally include a certain amount of research work and the student will get deeper knowledge in the subject he or she decides to major in. After four years, a BA student should be able to enter a research degree programme directly depending on how well he or she has performed… However, master’s degree programmes will continue to function as they do, following which student may choose to carry on for a PhD programme,” said scientist and former UGC chairman V S Chauhan.

How will school education change?

What impact will doing away with the M Phil programme have?

Chauhan said this should not affect the higher education trajectory at all. “In normal course, after a master’s degree a student can register for a PhD programme. This is the current practice almost all over the world. In most universities, including those in the UK (Oxford, Cambridge and others), M Phil was a middle research degree between a master’s and a PhD. Those who have entered MPhil, more often than not ended their studies with a PhD degree. MPhil degrees have slowly been phased out in favour of a direct PhD programme.”

Will the focus on multiple disciplines not dilute the character of single-stream institutions, such as IITs?

The IITs are already moving in that direction. IIT-Delhi has a humanities department and set up a public policy department recently. IIT-Kharagpur has a School of Medical Science and Technology. Asked about multiple disciplines, IIT-Delhi director V Ramgopal Rao said, “Some of the best universities in the US such as MIT have very strong humanities departments. Take the case of a civil engineer. Knowing how to build a dam is not going to solve a problem. He needs to know the environmental and social impact of building the dam. Many engineers are also becoming entrepreneurs. Should they not know something about economics? A lot more factors go into anything related to engineering today.”

No comments:

Post a Comment